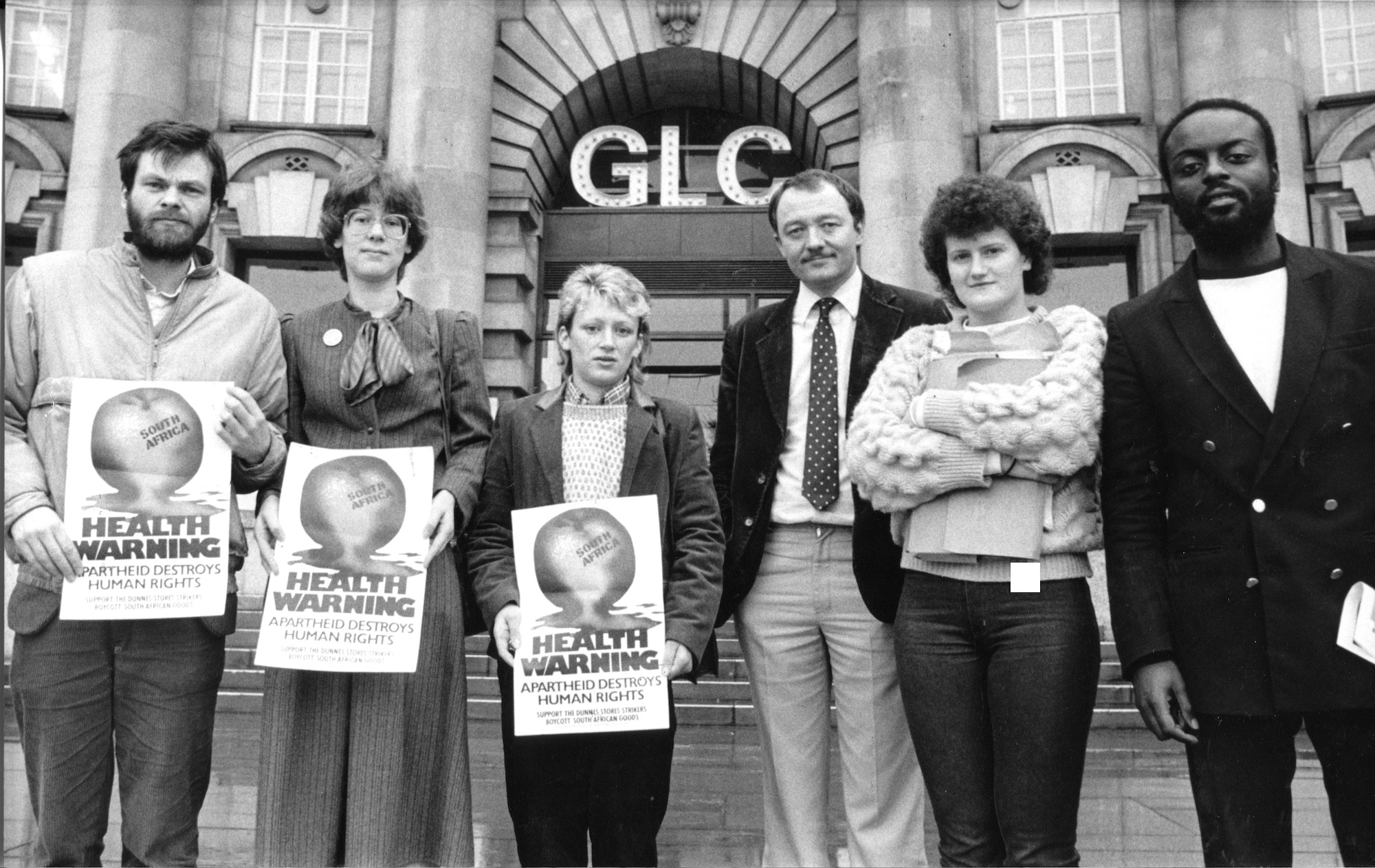

In Parts 5 and 6 of his blog, SIMON SAPPER tells how he travelled round Britain with Mary Manning and Cathy O’Reilly, workers at Dunnes Stores in Dublin, who went on strike rather than sell South African grapefruit. And of how much he learnt from the Anti-Apartheid Movement’s Executive Secretary, Mike Terry.

8000 miles away but still in your face

My time at AAM was priceless. Yes, it was often precarious and fragile. We had four phone lines and the calls could be incessant. Sometimes I would go and hide in the makeshift toilets, until someone invariably came and banged on the door.

Office life could go from the dangerously surreal – petrol being poured through our letter box late one night, followed by lighted matches – to the unbelievably bizarre. The Monday morning after we had put a quarter of a million people on Clapham Common for the Artists Against Apartheid gig, I opened up the office, only for a truck to thunder down Mandela Street five minutes later, knocking the burglar alarm off the wall.

Fortunately, it was an old-fashioned hammer-and-bell job, dampened down thanks to one step-ladder and half a dozen tea towels.

Our constant companion, at least early on, was the South African media. They devoured almost everything we put out, their readers apparently held in aghast awe at the enmity being ranged against them from 8000 miles away. The daily cuttings were a cheerful antidote to the uneven coverage in the UK press (although when my criticism of a shadow Cabinet member who sat on the board of a UK heavy-investor in South Africa was printed in the Mail on Sunday, I had an angry Peter Mandelson on the phone, thanking me for ‘kicking the party in the teeth’. Hmmm. The Pretoria government eventually realised what we had known all along – this was great PR for the liberation struggle – and banned newspapers from mentioning us.

The campaigning experience from AAM has stayed with me and was a stupendous apprenticeship. This was the practical application of the age-old trade union principle of solidarity – how it could be achieved, why some believed it to be irrelevant or unimportant, and the impact it had on both oppressors and oppressed.

It was epitomised by Mary Manning, Cathryn O’Reilly and their colleagues on the check-outs at Dunnes stores in Dublin. Their union, IDATU, had voted to support the call for sanctions. Mary and Cathryn took it literally. Dunnes suspended them over a refusal to process Outspan grapefruit. The strike rumbled through the summer and winter of 1984. Dunnes wasn’t closed down, and rather like, but much less spectacularly than, their also in-dispute miner-counterparts across the Irish Sea, this was a matter of attrition.

Bishop Desmond Tutu popped in to say hello on his way from Cape Town to Oslo to collect his Nobel Peace Prize. 'You must come and see me in SA’, he said, generating publicity and energy to sustain the dispute further.

Working with our local groups and counterparts in Ireland, we put together a tour of Britain for Cathryn and Mary. I was their facilitator, fixer and chauffeur. In council offices, bus depots, students’ unions – we met union members and local reps who ‘got it’. That sometimes you have to take a risk for something you believe is right. That once you step over that line, you can never be quite sure what is going to happen. That there’s not always a clear next step or easy closure. The essence of struggle, of resistance. We met not one person who couldn’t understand why they had said ‘Sorry, no’ to customers wanting to buy apartheid fruit.

And Mary and Cathryn were not physically imposing. Their presence didn’t fill the room – until they started speaking. But that was the point. They were just ordinary people doing ordinary jobs. Until something extraordinary came along. Off they flew to Jo’burg to take up the Bishop’s invitation – where they were denied entry, locked up and sent home. I went to meet them off the plane at Heathrow and we had sorted out rooms at an airport-side hotel for them to rest up. Cathryn’s little daughter had already been pictured with a ‘Let My Mummy Go’ placard.

It was real ‘quiet in the eye of the storm’ stuff. A row in South Africa, a cause celebre and political storm in Ireland. Nothing in the UK. In 1987, Ireland became the first ‘first world’ state to ban imports of South African produce. Mary had a street named after her in Jo’burg, and she and her colleagues met Mandela when he visited Dublin in 1990. He said of the strikers that they were ‘ordinary people far away from the crucible of apartheid [who] cared for our freedom’.

Moving on

I can’t really end this story without a word or two in appreciation of Mike Terry, AAM's Executive Director, and the person who gave me this amazing opportunity.

I’d never met anyone like Mike before. He had an amazing ability to keep so many balls in the air simultaneously –whilst at the same time looking like he was going to drop many of them. Then there was the challenge of running and leading a small organisation with many, sometimes disparate, heavily invested stakeholders during a period of explosive expansion in the UK and increased violence and repression in Southern Africa. He was also a powerful inspiring public speaker. It was a privilege to work with him and learn from him.

Well, Mike’s deputy, the formidable Cate Clark, moved on to other things in the summer of ’86. I covered the post and there was some talk about me doing so permanently – but I had reached a fork in the road, and wanted to go forwards in a different way. It was the British labour movement that held me in its thrall. That November, I moved to the augustly-named Institution of Professional Civil Servants – at 24, the youngest national official of any union in the country at the time.