In Parts 3 and 4 of his blog, SIMON SAPPER remembers the hard work involved in getting trade unions to sign up to economic sanctions against South Africa and tells the inside story of the AAM’s mega Trafalgar Square sanctions rally in November 1985.

Plans and organisation

If the realpolitik was a vital, delicate, dynamic learning curve, other parts of my job were just a mess.

Take the pre-digital age paperwork. Many trade unions had taken the decision to affiliate years ago, but we hadn’t billed them in a while. There had been a significant gap between the departure of my predecessor, Chris, and my arrival. Getting the files and finances in order brought instant benefit – or relief, given the state of our cash-flow. This was proof of the equation ‘Plans without organisation are just dreams’.

Powered up by now knowing who our union supporters were – and so where to concentrate effort on new recruitment, I toured union conferences, setting up stalls, leafleting delegates and trying to put together fringe events. The conference season generally ran from Easter to mid-June every year. I criss-crosssed the country – Eastbourne, Brighton, Scarborough, Blackpool, Bournemouth, Inverness. They all blended into one apart fromInverness!

We’d also managed to get a sympathetic motion on the agenda of most conferences. Sometimes there was a sharp reminder that not everyone was onside: there was no discussion on the floor of the Banking, Insurance and Finance Union conference one year, when ''next business'' was successfully moved as the debate on apartheid was called by the Chair.

It was all very frenetic and yet there was a clear underlying plan. We needed as much support as possible for our Sanctions Declaration – a commitment to economically isolate apartheid, something so far resisted by the government and also, frustratingly, the TUC (whose position then was to encourage UK companies investing in South Africa to adhere to certain employment standards).

The declaration was aimed at the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in the Bahamas that October. The agitation and pressure finally tipped the balance of forces inside the TUC. General Secretary Norman Willis signed on behalf of nearly ten million members. Mike presented me with the original, saying he thought I might appreciate it more than Sir Lyndon Pindling. The heads of government did, however, agree some limited sanctions.

This sort of activity was replicated across other strands of our work – political parties, local authorities and local anti-apartheid groups, and students. Labour leader Neil Kinnock was very supportive, contact facilitated by my predecessor, Chris Child, who was now working in his Westminster Office. Chris also introduced me to Glenys Kinnock, then heading up the One World charity. A fair number of Conservative activists also made contact, mostly quietly, unhappy with their party’s position. One slipped me the directory of all local associations and their officers. Just being able to contact that whole vital layer of the Conservative organisation in a co-ordinated way was an important message in itself.

The March against Apartheid

All of this was bubbling, binding and building towards what we hoped would be a huge national demonstration. A focal point for anger, frustration and activity. Over the summer we started thinking about the what, the why and the how. A march and rally? Sounds right. London – yes. Trafalgar Square – of course. With its natural boundaries, historical identity as a place of protest, and reviled neighbour, South Africa House.

The story of organising for what became a massive march and demonstration has been dramatised by the remarkable Ochenta storytellers, with an accompanying blog post here. But the story is worth re-telling.

It takes 30,000 people to make the Square look reasonably full. We took soundings, especially from local AA groups. We reckoned we could do that – but then we thought about how we could do things a big differently. Somehow, the notion of three feeder marches converging on the square emerged and firmed up.

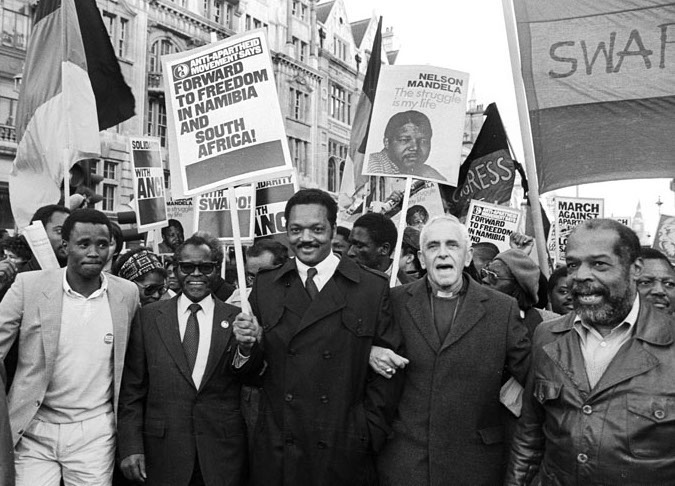

ANC and SWAPO were both consulted and gave their blessing. Both organisations’ Presidents – Oliver Tambo and Sam Nujoma – agreed to speak. One of our oldest and best trade union friends, Ken Gill would be there and the then President of Congress. Glenys Kinnock would speak for the development movement.

Once we hit October, it felt like we had found fourth gear. Publicity material started to arrive in our iconic back-and-white style. We needed to order more and then more again. Bold red, blue and yellow colour A3 and A2 posters appeared as if out of nowhere at the now renamed Mandela Street.

Two weeks to go and we moved from not daring to think of failure to a growing realisation that we would hit our numbers – probably. It wasn’t just the flyposting. The response from local branches – Bristol, Sheffield, Brighton and beyond – was solid. More than solid. We didn’t have to chase them, they were phoning us to confirm coaches booked and passengers confirmed. And then phoning us again to say those numbers had been superseded.

And then we heard Jesse Jackson was coming. More of that later. We had stuff to do. And two of the things on my list was police liaison and stewarding.

The boys – and girls – in blue first. And I’ve got to say, the discussions were perfectly civilised and practical. Commander Alec Marnoch was our man. His concerns were all about routing, timing, did we have enough stewards, what was the scope for disruption? And we were expecting a bit of bother, to be honest. One of the marches was going straight up Whitehall, passing Downing Street as it did so. It's not rocket science to work out that was one likely flashpoint.

This was where the stewarding arrangements would be crucial. In those days, the go-to was Chris Easterling, a national official for one of the civil service unions and the epitome of the word “solid” in every sense. And if Chris was solid, then the present and former dockers who formed his stewarding team were an even bigger version of him.

Almost too quickly the day arrived. It wasn’t raining and it wasn’t cold. No mobiles, no internet. As I recall, just a few erratic walkie-talkies. Trafalgar Square started to fill up at around the time the three feeder marches moved off. On the plinth of Nelson’s Column, I could see down Whitehall, Northumberland Avenue and St Martin’s Lane – the three approach routes.

But for now my concerns were more immediate. We didn't have enough people, stewards, to keep the plinth clear. Quickly we reorganised. The space at the front, facing the square, was where the speakers would gather. The space to the left, and on the ground between the westerly two of Landseer's lions, was where the control van drew up. We soon acquired squatters on the right-hand side of the plinth, including some lefty activists I hadn't seen since York, but it was all good-natured. Thank goodness.

We neared the time when we expected the feeder marches to arrive. The square was now comfortably full. Like water in a flume, you could see a disruption before the marches came into view. And like a distant thundercoming closer, you could hear them too.

With glorious symmetry, these tidal noisy colourful processions tumbled out of St Martin's Lane, past the National Gallery, mixing and swirling with the main march as it rolled out of Whitehall,closely followed by the crowd from Northumberland Avenue. I barely had the words to describe it, but I was able to tell people that they were part of the biggest ever demonstration against apartheid in Britain, probably Europe, and maybe further afield too.

Front and centre were the flags of ANC and SWAPO but in that area to the right was a cluster of red-yellow-green Rastafarian tricolours. All eyes were on the microphone. We knew we had to manage this carefully. A quick huddle and we agreed Jesse Jackson – who had spoken already – would round off the rally with a call-and-respond with the crowd on along the lines of “I am somebody. You are somebody, we are all somebody. Free Nelson Mandela”. The sound would then be cut.

But before we got there, I saw a couple of placards fly through the air outside SA House. There was clearly a scuffle going on. Then, oh Lord, a crash barrier followed the placards. A couple of blue lights start flashing and moving. You would seen it or been aware unless you were close by, and the trouble seemed to move up and round the corner. My attention came back to what the Rev. Jackson was saying. You could have heard a pin drop. He gave the last call, I shut off the sound.

And we all breathed out.

The speakers exited stage left. The stewards relaxed and started to gather in chairs and flags. Chris told us how a group of around 80 near the head of the Whitehall March had simply sat down outside Downing Street. A few verbals with the heavy police presence there that weren’t reciprocated. The stewards guided the march around them and it all moved on.