LUTHULI’S APPEAL

The Anti-Apartheid Movement began as the Boycott Movement, set up in 1959 to persuade shoppers to boycott apartheid goods. It invoked Chief Albert Luthuli’s appeal for an international boycott of South African products.

For 35 years the consumer boycott was at the heart of anti-apartheid campaigns. Hundreds of thousands of people who never attended a meeting or demonstration showed their opposition to apartheid by refusing to buy goods from South Africa. Boycotting South African fruit and other products was something that everyone could do.

‘LOOK AT THE LABEL’

The first Boycott Movement leaflet listed South African fruit, sherry and Craven A cigarettes as goods to avoid. The AAM regularly updated its lists of South African brand names, asking shoppers to ‘Look at the Label’. With the growth of supermarket chains like Tesco and Sainsbury’s, it campaigned to stop them stocking South African products and organised days of action outside local shops.

As South Africa diversified its exports in the 1980s, the AAM focused on fashion chains like Marks and Spencer, Next and Austin Reed. Next and the Co-op Retail Society stopped selling South African goods. Between 1983 and 1986 British imports of South African textiles and clothing fell by 35%. In June 1986 an opinion poll found that 27% of people in Britain boycotted South African products.

PEOPLE’S SANCTIONS

When Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher undermined international sanctions in the mid-1980s, the AAM recast the boycott campaign as a call for ‘people’s sanctions’. In 1989 its Boycott Bandwagon, a converted double-decker bus, took the message to cities and towns all over Britain. The campaign spread to gold, coal and tourism, and anti-apartheid activists targeted the South African and Namibian stands at the World Travel Market at Olympia.

CAMPAIGN SUCCESS

The boycott was one of the most successful of all the AAM’s campaigns. It was only lifted in September 1993 after South Africa was irrevocably set on the path to democratic elections.

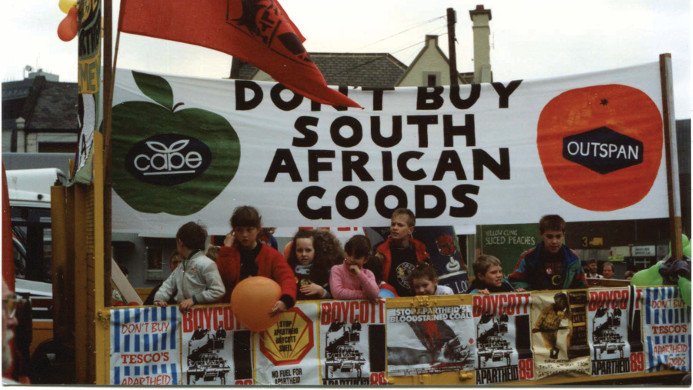

Sheffield AAM supporters outside Tesco on 13 October 1989. Over 2,000 shoppers signed Sheffield AA Group’s petition asking Tesco to stop selling South African goods. Earlier in the year, 320 of Tesco 380 stores all over Britain were picketed in a special Day of Action on 22 April. Copyright © Martin Jenkinson Image Library

Sheffield AAM supporters outside Tesco on 13 October 1989. Over 2,000 shoppers signed Sheffield AA Group’s petition asking Tesco to stop selling South African goods. Earlier in the year, 320 of Tesco 380 stores all over Britain were picketed in a special Day of Action on 22 April. Copyright © Martin Jenkinson Image Library