ALL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN AFRICA

The 1970s were a pivotal decade in the struggle for freedom in Southern Africa. In 1975 Mozambique and Angola won their independence from Portugal. In Zimbabwe the guerrilla war escalated, forcing the white minority to concede majority rule. In South Africa the Soweto student uprising in 1976 and the growth of independent trade unions signalled a new wave of resistance.

Britain was preoccupied with domestic economic problems and the cold war against the Soviet Union. The Anti-Apartheid Movement became identified with the left in British politics and came up against a hostile media. Nevertheless it engaged with government and put down deep roots in the student and trade union movement.

ARMS EMBARGO

In 1970 the Conservative government announced the lifting of Britain’s partial arms embargo against South Africa. The AAM led protests that ensured no major armaments were supplied. In 1977, after the banning of the Christian Institute and black consciousness organisations in South Africa, the UN Security Council imposed a mandatory arms ban. The AAM set up the World Campaign against Military and Nuclear Collaboration with South Africa to ensure the ban was fully enforced.

DISINVESTMENT

Barclays Bank was the main target of AAM action to persuade British companies to pull out of South Africa. Other companies came under fire as stakeholders put pressure on universities, trade unions and churches to sell their holdings. In 1973 British companies hit the headlines because of the poverty wages they paid their black South African workers. The AAM argued against the ‘code of conduct’ approach that called for British firms to pay higher wages rather than pull out.

REPRESSION

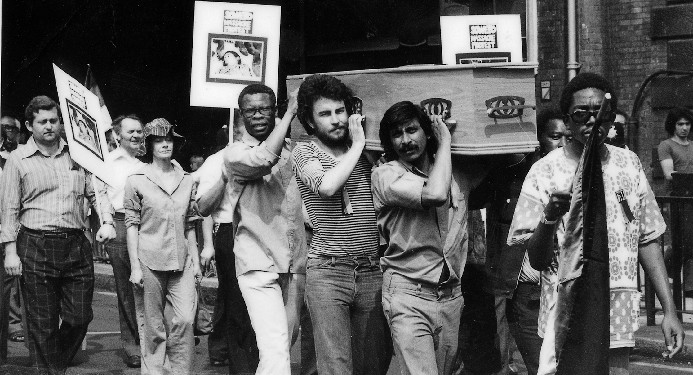

In 1973 the AAM joined with the International Defence and Aid Fund and other groups to set up Southern Africa the Imprisoned Society (SATIS). SATIS supported political prisoners and campaigned for their release. From the early 1970s, the apartheid authorities stepped up arrests of political activists. Some detainees were tortured to death, and the murder of Steve Biko in 1977 was met by worldwide protests. In 1979 SATIS led an international campaign to overturn the death sentence on Solomon Mahlangu, a young freedom fighter. Mahlangu was hanged, but the apartheid government was served notice that political executions would provoke international opprobrium.

By the end of the decade resistance was growing inside South Africa and guerrillas from the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) were entrenched in northern Namibia. In Britain it was unclear how the new Conservative government would respond. The Anti-Apartheid Movement had come through a difficult decade and was building a support base that would help it meet the challenges of the 1980s.

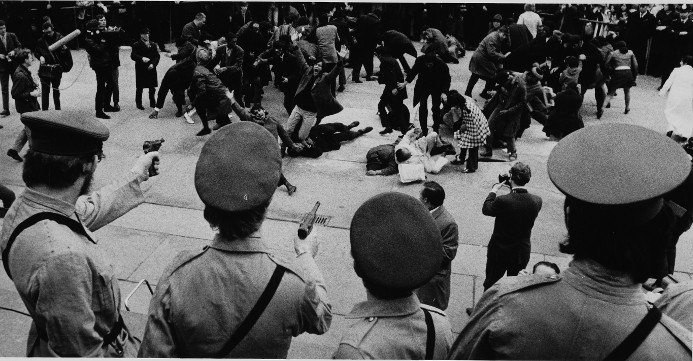

On the tenth anniversary of the Sharpeville massacre the Anti-Apartheid Movement staged a re-enactment in Trafalgar Square. Around 3,000 people watched as actors dressed as South African police took aim and people in the crowd fell to the ground. The event was organised jointly with the United Nations Students Association (UNSA).

On the tenth anniversary of the Sharpeville massacre the Anti-Apartheid Movement staged a re-enactment in Trafalgar Square. Around 3,000 people watched as actors dressed as South African police took aim and people in the crowd fell to the ground. The event was organised jointly with the United Nations Students Association (UNSA).

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ABOUT THE AAM IN THE 1970s

The cancellation of the all-white South African cricket tour in June 1970 was a victory for the Anti-Apartheid Movement. The AAM looked forward to building on this success by stepping up its campaign to end British trade and investment in South Africa. But the unexpected Conservative victory in the June 1970 general election once again threatened Britain’s partial arms embargo. The new Prime Minister, Edward Heath, announced that his government intended to resume arms sales to South Africa. Heath had misjudged public opinion. The same broad coalition that had stopped the ’70 tour rallied to save the embargo. A 1971 Gallup poll found that half the British public opposed arms sales to South Africa. An AAM Declaration in support of the arms ban was signed by 100,000 people in six weeks. In October, 10,000 marched behind a model Buccaneer bomber to a rally in Trafalgar Square. AAM leader Abdul Minty flew to Singapore to present the Declaration to the 1971 Commonwealth Prime Ministers Conference. Although the government never publicly reversed its decision to resume arms sales, the only equipment it supplied were seven Wasp helicopters.

CAMPAIGNING FOR DISINVESTMENT

South Africa had industrialised fast in the 1960s and nearly every major British company had a subsidiary in South Africa. Except for Barclays and Shell, the AAM did not campaign for a consumer boycott of individual companies. Instead it called for disinvestment. The disinvestment campaign had three strands: exposure of how individual British companies profited from apartheid; attempts to persuade institutions to sell their shareholdings in the companies; and a call for the British government to curb new investment and loans to South Africa.

In the early 1970s there were some high profile successes. Students led the campaign. By the 1972 autumn term, students at over half Britain’s universities were taking some action to persuade their colleges to sell shares. At Manchester University students held a mass sit-in; after three years of protests the university agreed to disinvest. The 1971 TUC annual congress urged affiliated trade unions to ensure they had no investments in British companies that owned South African subsidiaries. The Church of England’s Church Commissioners sold shares in the mining conglomerate Rio Tinto Zinc. Share sales never took place on a scale sufficient to impact on companies’ capital assets, but they had a considerable propaganda effect.

Barclays was South Africa’s biggest high street bank. In 1972 anti-apartheid activists disrupted its annual general meeting and won national press publicity. Student unions banned Barclays stalls from their freshers fairs and some local authorities, like Camden, withdrew their accounts. Barclays was an easy target, with branches on every high street. The AAM held national days of action, when local supporters picketed branches asking customers to close their accounts.

CONSTRUCTIVE ENGAGEMENT

British companies countered the AAM’s disinvestment campaign with the argument that economic growth, rather than political struggle, would bring apartheid to an end. The argument was supported by groups who genuinely deplored apartheid, but feared the revolution and economic disruption they thought disengagement would bring. Instead of pressing British companies to withdraw, they asked them to pay higher wages to their black workers and dismantle the colour bar by training black employees to do skilled jobs. The argument was boosted by a front-page exposé by Guardian journalist Adam Raphael of British firms that paid poverty wages. His articles implied that companies should be shamed into paying higher wages rather than close their subsidiaries. A House of Commons committee proposed a code of conduct for companies operating in South Africa. A TUC mission to South Africa in 1973 recommended disinvestment, but only by companies that were hostile to independent trade unions. The AAM was wrong-footed and for a time spent as much energy rebutting arguments for constructive engagement as taking initiatives to encourage withdrawal. The ‘code of conduct’ approach was taken up in the European Economic Community (EEC) and by the adoption of the Sullivan Principles in the USA. By the end of the decade it was overtaken by the upsurge of opposition to apartheid within South Africa that made clear that ‘reform’ was no longer an option.

POLITICAL PRISONERS

In the spring of 1969 reports trickled out of South Africa of new arrests under the Terrorism Act. Twenty-two people, among them Winnie Mandela, were charged. Former South African political prisoners living in exile in Britain protested outside South Africa House. Campaigning for political prisoners became one the AAM’s main activities. Its initiatives complemented the vital undercover work done by the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) in funding defence lawyers in political trials and providing financial support for prisoners’ families.

In December 1973 the AAM joined with IDAF and other organisations to form Southern Africa the Imprisoned Society (SATIS), an umbrella group that campaigned for political prisoners throughout Southern Africa. SATIS was set up to publicise the harsh conditions suffered by long-term prisoners. It prefigured the later campaign for the release of Nelson Mandela by asking local groups to adopt individual prisoners. This initiative was overtaken by the new wave of repression unleashed against students and the black consciousness movement. When members of the South African Students Organisation (SASO) were arrested in the autumn of 1974, SATIS orchestrated the sending of hundreds of cards and telegrams to the South African authorities. As more people were rounded up, SATIS organised regular protests outside South Africa House. British students demonstrated in defence of student detainees, trade unionists protested at the arrest of fellow workers and performers like Kenneth Williams and Sheila Hancock picketed South Africa House in support of detained actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona.

In 1964 Babla Saloojee was the first person known to have been tortured to death by the South African Special Branch. In the mid-1970s reports leaked out about the torture of detainees. In May 1976 SATIS announced an emergency campaign to protest against the torture, with daily pickets of South Africa House for six weeks, joined by groups ranging from the Tory Reform Group to the Communist Party. The number of people who died in detention escalated. The following year, the death of Steve Biko provoked worldwide protests. The AAM rejected the inquiry instigated by the South African authorities as a cover-up and proposed an international inquiry. The call received wide backing and Foreign Secretary David Owen attended a memorial service for Biko arranged by IDAF in St Paul’s Cathedral. On the first anniversary of Biko’s death SATIS hung a banner with the names of all the detainees murdered by the Security Police from the roof of St Martin’s in the Fields. Inside the church a service celebrated Biko’s life.

LIBERATION IN MOZAMBIQUE AND ANGOLA

The liberation of Mozambique and Angola from Portuguese colonial rule in 1975 transformed the long-term prospects for the freedom struggle in the rest of Southern Africa. Facing defeat in Portugal’s African colonies, the Portuguese army overthrew the dictatorship of President Marcello Caetano. For the first time Zimbabwean guerrilla fighters had a friendly border through which they could infiltrate from the east. Guerrillas from the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) had easier access to northern Namibia, and Angola hosted training camps for the ANC’s armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe. The victory of FRELIMO in Mozambique and MPLA in Angola gave a huge psychological boost to black South Africans.

But the coming to power of Marxist governments in Mozambique and Angola propelled Southern Africa into the frontline of the cold war between the West and the Soviet Union. In 1975 Cuban troops arrived in Angola to help the new MPLA government fight off a South African invasion. In 1978 the UN Security Council passed Resolution 435, setting up a Western ‘contact group’ to negotiate on independence for Namibia. The talks dragged on, with the USA insisting on the withdrawal of Cuban forces from Angola as a precondition of Namibian independence.

THE SOWETO UPRISING

On 16 June 1976 school students marching through Soweto were shot down by police. They were protesting at plans for teaching in Afrikaans and chronic overcrowding in schools. The shootings triggered a wave of student demonstrations and worker stay-at-homes that engulfed South Africa. The AAM hailed the uprising as the most significant event in South Africa since Sharpeville in 1960. It urged the British government to respond by ending all military links with South Africa and supporting a UN mandatory arms embargo. But the immediate reaction to the Soweto uprising in Britain was more muted than the response to the shootings at Sharpeville 16 years before. The mass demonstration the AAM organised in solidarity with the students on 27 June was relatively poorly attended. The AAM’s new ‘No Arms for Apartheid’ petition was signed by around 64,000 people – fewer than the 100,000 who signed the declaration calling on the Conservative government to maintain the arms ban in 1970. This was largely because in the mid-1970s Britain was preoccupied with cuts in public expenditure and record post-war unemployment. Within South Africa the Soweto uprising signalled a new mood of resistance that neither reform nor repression could suppress. In the longer term this created a new context for the international solidarity movement. In Britain, from the late 1970s, it raised the profile of the anti-apartheid struggle and gave a big boost to AAM campaigns.

INDEPENDENT TRADE UNIONS

South African workers had a long history of trade union organisation. But in the 1960s the non-racial trade union federation SACTU (South African Congress of Trade Unions) was suppressed by the apartheid government. SACTU leaders were gaoled or went into exile. In 1973 workers in Durban went on strike against poverty wages. The strikes were the start of the growth of independent trade unions which gathered strength through the 1970s.

The AAM worked with British trade unions to organise support for their sister unions in South Africa. It publicised disputes over union recognition and strike action, especially when they involved the subsidiaries of British companies. A prominent case was that of the British owned company Smith and Nephew. The firm led the way in recognising an independent South African union, the National Union of Textile Workers, but in 1977 it withdrew recognition. After South African workers went on strike and unions overseas mounted an international campaign, the company reversed its decision.

The AAM worked closely with SACTU. But the new union movement in South Africa had disparate ideologies and traditions. Some unions were set up with support from left-wingers from within TUCSA unions, some by black consciousness movement supporters and some were former SACTU affiliates. Some of the new unions argued that trade unions should stay out of the political struggle. In Britain, the AAM broadly supported SACTU’s claim to be the ‘gatekeeper’ of links between British and South African unions. This led to disagreements that were only resolved when the majority of the new unions came together to form the Congress of South African Trade unions (COSATU) in 1985.

SUPPORT FROM BRITISH TRADE UNIONS

From its formation, the AAM had a vision of building a broad civil society coalition united in opposition to apartheid. One of the main constituencies it looked to was the British trade union movement. The AAM had very little trade union support in the 1960s, with the important exceptions of the draughtsmen’s association DATA and a few other small craft and media unions, such as the Musicians Union. The TUC, which had strong links with the predominantly white Trade Union Council of South Africa (TUCSA), rejected sanctions and was suspicious of the AAM because of its links with SACTU.

The AAM’s strategy was to work at all levels of the union movement, promoting resolutions at TUC annual congress and national union conferences, and prompting union leaders to take action on consensus issues like support for political prisoners. It asked unions to join the AAM. In 1971 14 national unions were affiliated. There was a big increase after the Soweto uprising, with five new unions affiliating in 1977 and another nine in 1978. By 1980 35 national trade unions were affiliated. The AAM’s small Trade Union Action Group, set up in 1968 by volunteers with no standing in the labour movement, was transformed into a committee of delegates who reported back to their unions.

The TUC remained a battleground, with unions sympathetic to the AAM winning congress votes for economic disengagement, while the TUC International Department pursued a policy of constructive engagement. In 1971 a wide-ranging congress resolution deplored arms sales to South Africa; asked affiliated unions to disinvest from British companies that owned South African subsidiaries; pledged support for the liberation movements; and called on the British government to curb new investment in South Africa. There was little overt opposition to this: the problem was how to make the TUC International Department implement it. The AAM tried to use TUC resolutions to promote union action. In 1976 and 1977 the International Congress of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) and an international conference held by the International Labour Organisation called for international weeks of action on South Africa. The AAM used the TUC’s request to trade unionists to take part in the weeks of action to press the call for sanctions, leaving the TUC to ask union members to ‘uncover the facts’ about the pay and conditions of South African workers. The AAM campaigned against emigration to South Africa and tried to persuade the TUC to give a lead on this, but with only patchy success.

At the same time the AAM worked to build support for its policies of sanctions and boycott at the grassroots. Towards the end of the 1970s, there was conflict within the AAM over the emphasis that should be given to campaigning for worker direct action, with left groups putting motions ‘resolving to work towards a significant level of industrial blacking of South African imports’ to the AAM’s 1977 annual general meeting1. The majority view was that the AAM should concentrate on building an understanding of the need to isolate South Africa rather than on asking specific groups to refuse to handle South African goods. The AAM welcomed direct action, but it recognised that workers were preoccupied with defending their own working conditions and might be reluctant to take action that could put their jobs on the line.

STUDENTS

The AAM’s first success in winning unequivocal support for its policies in a mass membership organisation was in the student movement. In 1970 the National Union of Students (NUS) conference called for a total educational, cultural and sporting boycott of South Africa. The following year, the NUS joined forces with the AAM to set up a network of student activists. Starting in July 1972, the network held an annual conference at which nearly all Britain’s major colleges and universities were represented. Like the AAM, the network had a two-pronged strategy: it campaigned in support of the liberation movements and anti-apartheid groups within South Africa, and against all links with South Africa. Students organised protests against the arrest of student leaders in South Africa and took action to persuade their own colleges to sell shares in firms with South African interests. The NUS set up a Southern Africa liberation fund and unions at many universities raised money for scholarships for South African students. Over the decade, thousands of students took part in anti-apartheid campaigns, building a reservoir of people who later took up anti-apartheid issues in their jobs and professions.

THE BRITISH CHURCHES

Another important constituency to which the AAM looked for support was the British churches. Like the TUC, they had strong links with their sister organisations in South Africa and in the 1960s were guided by the white-led South African churches. This changed when ‘prophetic’ anti-apartheid leaders like Desmond Tutu and Allan Boesak began to transform the voice of the churches within South Africa. For many years the British churches spoke out against arms sales and repression within Southern Africa, but opposed economic sanctions. In 1972, the World Council of Churches urged its members to press international corporations to withdraw from South Africa, but the British Council of Churches (BCC) blocked moves to set up a special unit to discuss action. Instead, it was left to an ad hoc body, Christian Concern for Southern Africa (CCSA), to act as a forum for discussion. For most of the 1970s, the churches followed a policy of constructive engagement. Of the individual denominations, the Methodist Church and the Church of Scotland were by far the most proactive.

In their consultations with South Africans in the 1970s, the churches in Britain leaned towards the black consciousness movement, to the exclusion of the liberation movements. Seminars and consultations organised by the BCC and the Church of England’s Board of Social Responsibility invited representatives of the Black Allied Workers Union and the Black People’s Convention, but never the ANC or PAC. The AAM was acutely aware of these differences. It pursued a two-track approach of working with the churches on consensus issues like the arms embargo and putting the case for economic disengagement. It accepted invitations to participate in church-sponsored discussions and invited staff members of the churches’ international policy departments to AAM meetings. It also tried to initiate dialogue between the churches and the liberation movements: in June 1979 it wrote to the General Secretary of the British Council of Churches suggesting a meeting with Oliver Tambo.

The banning of the Christian Institute in October 1977 provoked a sharp reaction from the British churches. Towards the end of the decade their attitude began to change in response to appeals from the radicalised leadership of the South African churches. The BCC’s 1979 General Assembly marked a significant change in attitudes when the Assembly adopted a policy of ‘progressive disengagement’2 . Although this still fell far short of the economic sanctions advocated by the AAM, the way was opened for much closer co-operation. Helped by meetings with the staunchly Anglican Oliver Tambo, church attitudes towards the ANC also changed. When its London office was bombed by apartheid agents in March 1982, the BCC offered temporary accommodation to the ANC’s Information Department. Individual church people began to play a part in AAM conferences, discussing how religious groups could join anti-apartheid campaigns. This was a small beginning, but one which heralded the transformation of the solidarity movement in the 1980s.

THE 1974–79 LABOUR GOVERNMENT

From 1974 to 1979 the AAM once again faced a Labour government. The new administration announced it would comply with the UN arms embargo and withheld the last of the Wasp helicopters sold to South Africa under the Conservatives. In the summer of 1975 it announced the termination of the Simonstown Agreement, which gave British warships naval facilities in the Cape. But it gave the go ahead to joint naval exercises with South Africa. Its definition of the equipment covered by its arms ban excluded almost everything that had dual military-civilian use. The government was even reluctant to take action to ensure South Africa could not develop a nuclear bomb. In the face of compelling evidence to the contrary, Foreign Secretary David Owen told a Labour MP: ‘In August 1977 Mr Vorster gave public assurances that South Africa did not have and did not intend to develop nuclear explosive deliveries …’.3

In its first few years, the government made no move to cut trade and investment with South Africa or even to stop nationalised industries like the British Steel Corporation expanding their stake. After he succeeded Wilson as Prime Minister in 1976, James Callaghan wrote: ‘When I became Foreign Secretary in March 1974 instituted a review of South African relations. One of its conclusions was that we should not interfere with our normal civil trading links with South Africa.’4

The AAM lobbied the government unremittingly, presenting detailed memoranda on breaches of the arms embargo and requesting meetings with the Foreign Secretary and other ministers. It exposed NATO collaboration in the construction of a secret underground naval surveillance system, Project Advokaat, at Silvermine in the Cape. In March 1975 it organised a mass demonstration against the naval exercises and military collaboration.

After the Soweto uprising, the government slowly changed tack. The new Foreign Secretary, David Owen, met AAM deputations twice in 1977 and agreed to investigate breaches of the government’s voluntary arms ban. Then in November 1977, in the aftermath of the banning of 19 black consciousness groups in South Africa and the death of Steve Biko, Britain dropped its UN veto and voted for a mandatory arms embargo under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Although the resolution had gaping loopholes, it was a huge step forward. The mandatory ban made it impossible for South Africa to upgrade essential weaponry, especially sophisticated fighter aircraft. Without the embargo, the Conservative government which returned to power in 1979 might well have resumed arms sales: but even Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher never reneged on the UN arms ban.

From 1977 the Labour government began a tentative rethink of its attitude to trade and investment in South Africa. David Owen judged that political unrest was making investment there ‘econmically risky’5. At a meeting called by the AAM-sponsored International Anti-Apartheid Year Committee in January 1979, he defended the code of conduct approach, but said that the government had ‘shown a determination to start on the difficult path of reducing our economic profile and economic commitment in South Africa’6. Behind the scenes, Ministers were beginning to see South Africa as an unreliable ally and look ahead to how Britain could reposition itself in relation to independent Africa.

It is likely that if Labour had won the 1979 general election, in the face of escalating resistance in Southern Africa and growing solidarity in Britain, it would at least have begun to take measures to reduce Britain’s stake in the apartheid economy. But Labour was defeated in the May 1979 general election, for domestic reasons, at the very moment when its policy on Britain’s stake in South Africa seemed set to change.

BUILDING A BROADER BASE

The UN declared 1978 ‘International Anti-Apartheid Year’, with support from General Assembly members, including Britain. The AAM used the declaration to try and broaden its support and set up a coordinating committee that included the the British Youth Council and the British Council of Churches and other church organisations. As part of the Committee’s activities, the Tory Reform Group held a fringe meeting at the Conservative Party’s 1978 annual conference. In January 1979 the Committee hosted a meeting with Foreign Secretary David Owen as the main speaker.

Throughout the 1970s, the AAM worked to extend its own grassroots organisation. The number of local groups doubled to around 60, giving the AAM a presence in most major British cities. A Scottish Anti-Apartheid Committee was set up in 1976 to coordinate the work of local AA groups, trade unions and local auhorities. The AAM also reached out to women’s organisations and professional groups like architects and healthworkers. These had a ready campaign target in the links between their professional organisations and all-white bodies in South Africa.

THE 1979 GENERAL ELECTION

In May 1979 the Conservative Party won the British general election and Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister. Unexpectedly, one of the first actions of the new government was to convene talks on Zimbabwe which led to one person one vote elections and majority role. See Zimbabwe. This was of huge significance for the Southern African region. It also cleared the way for the Anti-Apartheid Movement in Britain to concentrate all its energy on campaigning for the independence of Namibia and an end to apartheid.

CONCLUSION

The 1970s were a pivotal decade in the struggle for liberation in Southern Africa. Mozambique, Angola and Zimbabwe won their independence. The UN initiated tortuous negotiations on Namibia which eventually led to independence in 1990. In South Africa, students and workers launched a new wave of resistance. It was becoming clear that apartheid was economically and politically untenable. In Britain the AAM was beginning to reach out to build a broad movement of opposition to apartheid. But at the moment when it seemed that real advances could be made in ending British support for South Africa, Britain elected a Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, who was implacably opposed to sanctions.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 16.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 2202, Anti-Apartheid News, June 1979.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 780, David Owen to Frank Hooley MP, 13 November 1978.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 779, James Callaghan to Jack Jones, 8 November 1976.

- AAM Archive, MSS AAM 780, Speech by David Owen to Cumbria County Labour Party, 17 March 1978..

- A copy of his speech is in the AAM Archive, MSS AAM 1379.

CLICK HERE FOR DOCUMENTS & PICTURES FROM THE 1970's

CLICK HERE TO READ ANTI-APARTHEID NEWS, 1970–79